6

Teacher Introduction:

From its earliest days as a territory, Colorado was home to communities of migrants. Native peoples like the Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho also led nomadic lives in and out of this region of North America. This chapter particularly examines the experiences of immigrants after the gold and silver rushes of the nineteenth century. What kinds of immigrants came to make Colorado home in the twentieth century? What motivated the decision to come? What challenges did they face?

Immigrants move because of push and pull factors. Some important push factors for Colorado immigrants included economic hardship at home, religious and political persecution, and distressed environments. Pull factors included job opportunities in Colorado, relative safety, and freedoms from abuse or violence. Many migrants celebrated the civil liberties and educational opportunities that they found in the state. The documents in this chapter allow students the chance to explore these push and pull factors.

From 1880 through 1924 more than 25 million immigrants moved to the United States. Encouraged by employers offering higher paying jobs than they could find at home, many immigrants came from southern and eastern Europe or Mexico in these years. This chapter considers initially the experiences of Italian, Mexican, and Russian-German peoples. Typically, immigrants in these years came to work in agriculture, food processing, or mining. The range of immigrants can help students see the diversity of the cultures and languages in Colorado’s history.

At times immigrants to Colorado confronted prejudice and suspicion. We include a few important examples here. World War I found German immigrants as special targets of suspicion. They maintained their language in schools and in churches in farming communities near Greeley in the north and around Rocky Ford in the south. When the United States joined World War I, the American government encouraged suspicions of German immigrants with the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917 and 1918. Colorado residents who had previously coexisted peacefully with German-speaking immigrants suddenly felt threatened in 1918. This led to an important test of civil liberties.

World War II again generated suspicions in the minds of native-born Euro Americans. In this conflict it was Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants who bore the brunt of these fears. Beginning in 1942 the US government mandated the relocation of 110,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants from California, Oregon, and Washington to places away from the Pacific Coast. About 7,000 of these residents were imprisoned for the duration of the war at the Amache camp near Granada in eastern Colorado. At this camp, Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were denied basic civil liberties. During their internment these forced immigrants to Colorado maintained some semblance of their normal lives, even organizing schools and sporting events for young people. Just how these forced migrants to Colorado would adjust and interact with existing residents was uncertain.

Last, this chapter includes examples of more recent efforts to resettle refugees in the state. Since the 1965 federal revision to immigration law, Colorado has welcomed a number of immigrants fleeing persecution or natural disaster in their homelands. The Cold War created new conditions for immigrants who sought refuge from communist countries. Many U.S. leaders were eager to welcome these refugees. The shift in immigration can allow students a chance to consider broad changes over the twentieth century. Again, the immigrant experience, with various push and pull factors, can organize students as they consider what a move to Colorado meant for refugees. They will likely encounter the children of these refugees if not refugees themselves in their classrooms.

Over the twentieth century many immigrants have moved into the Centennial State. Students in today’s classrooms will typically experience this first hand or will be immigrants or the children of immigrants themselves. What motivates immigrants to move to Colorado? How do they benefit existing communities in the state? How should native-born Coloradans respond? The reception that immigrants have received in the past raises important questions about how we might respond to immigration today. The sources in this chapter allow students to begin addressing these questions.

***

Sources for Students:

Document 1: Photograph of Italian Immigrants in New York, 1905

Around 1905 photographer Lewis Hine took this photo of Italian immigrants outside Ellis Island in New York. They had just arrived on a steamship from Europe and may have been heading to Colorado to work. Between 1880 and 1924 there were more than 25 million immigrants who moved to the United States. Hundreds of thousands of them migrated to Colorado and other states in the American West. The majority started from Eastern Europe (Poland, Russia, Germany) or countries like Italy in southern Europe.

[Source: Lewis Hine photograph, about 1905. Available at the George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive. Online image: http://www.geh.org/fm/lwhprints/htmlsrc/index.html]

Questions:

- What do you notice about the clothing and hats these men are wearing? Why might they wear ties or dress-up coats? What can their facial expressions tell us?

- Imagine they were planning to stay in the United States for many months if not years to work new jobs. What might they bring in those suitcases and bags?

- Do they look rich or poor to you? Why?

- What kind of work might these men be able to do in the United States? How could we find this out?

- The photographer, Lewis Hine, didn’t tell us what he was thinking when he took this picture. Why do you think he decided to photograph these men?

***

Document 2: Emilio Ferraro Interview, 1978

Emilie Ferraro traveled from his home in Gremaldi in southern Italy to Trinidad, Colorado in 1910. He crossed the Atlantic from Naples to New York in a steamship and then took the train straight to Colorado where he met three uncles. He immediately began looking for a job in Trinidad. This was his memory of that first day, told to an interviewer in 1978:

|

WORD BANK: Trade: a skilled job Pull ovens: a job working at a hot furnace to prepare coal for steel factories |

“when I came to Trinidad, I was looking for some shoe factory . . . because my trade was shoemaker. . . . I stopped at the shoemaker . . . [who] was an Italian fellow from Sicily. I said to him,” you give me work?”

“ Oh sure, I’ll give you work, [he said].”

“How much [will] you pay me?”

“ One dollar a day, [he said].”

How could I make a living? My uncle told me, no, no, no. . .. You come with me [to] Starkville. I [will] get you a job making two dollars a day. . . . And then if you learn how to pull ovens, you get 98¢ more. . . .And I started at Starkville working.”

[Source: Emilio and Gertrude Ferraro Interview, 1978. Colorado Coal Project Collection, University of Colorado Digital Collections: http://cudl.colorado.edu/luna/servlet/UCBOULDERCB1~76~76]

Questions:

- Why did Emilio Ferraro come to Trinidad. What did he hope to do there?

- Starkville was the site of a big coal mining operation just south of Trinidad. Why did Ferraro decide to take up coal mining work

- What was the difference in pay between a Trinidad shoemaker and someone who “pulled ovens” in Starkville?

- Look again the picture in Document 1. We don’t know the names of any of those men. Could one of them be Emilio Ferraro? Why or why not?

- Emilio Ferraro told this story about 68 years after it happened. How might that long period of time have affected his memory of that first day?

***

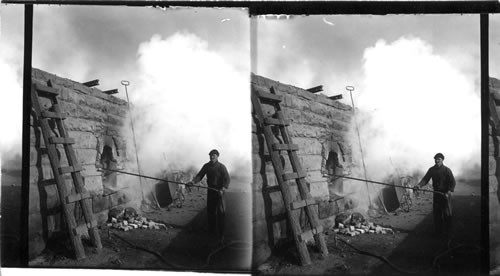

Document 3: “Pulling the oven” at Starkville, Colorado, about 1910

Here is a photograph of a man “pulling the oven” to heat coal up to a very high temperature. The end result of this process was the creation of “coke” which was a concentrated form of coal used to heat the blast furnaces in Pueblo that made steel.

[Source: unknown photographer around 1910. Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside. Available online: http://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt8n39p9t0/?order=2&brand=oac4]

Questions:

- This picture is from a coke oven in Starkville, Colorado. We don’t know the name of the man in the picture. Could it be the Italian immigrant from document 2? Why or why not?

- Why might the man need such a long pole to move coal around inside this oven?

- How might this work be dangerous?

- The previous document mentioned how much this work could pay. What was that amount?

- Why might an immigrant like Ferraro travel all the way across the Atlantic Ocean and the across most of the United States to take a job like this?

- Why do think the photographer decided to take this picture? What might have motivated him or her?

***

Document 4: Historian Thomas Andrews on wages for coal miners, 2008

Historians study primary sources to write about what happened in the past. Thomas Andrews carefully researched coal mining in southern Colorado and wrote about the money immigrants could earn doing that work:

|

WORD BANK: Rates and wages: a regular amount of money paid for a day’s work Prosperous: successful |

[Coal] companies often hired men with little or no experience underground. And unlike [many other businesses] coal corporations paid ‘Mexicans,’ Asians, and other nonwhites the same rates and wages as were paid to British Americans, an average of around…$15 a week by the 1910s. . . . [This was] at a time when . . . prosperous peasant families in Italy earned [between $50 and $100] per year.

[Source: Killing for Coal: America’s Deadliest Labor War (Harvard Univ. Press, 2008), pp. 105–6]

Questions:

- This source gives two different amounts that people could earn about 1910. How much could coal miners earn in Colorado per week? How much in a day, if they worked 6 days per week? How much could Italian peasants earn in a year?

- How can we compare those amounts to find out which was a better deal–coal miner or peasant?

- This reading tells us about a “Pull” factor, or a reason immigrants were drawn to Colorado. What kind of pull factor is this?

- Coal mining was dangerous work, with threats of tunnels collapsing and fires underground. How much money would you want to be paid to take on such a risk working underground?

- What kind of sources could Thomas Andrews have looked at to figure out these numbers?

***

Document 5: Interview with Alejandro Gonzales, 1987

In addition to mining, many immigrants came to Colorado around 1910 to work in the fields growing and harvesting sugar beets. These are plants like giant white carrots that can produce a sweet syrup. That syrup can dry to taste like table sugar. Growing and harvesting sugar beets was hard work, especially under the hot summer sun. Alejandro Gonzales was a sugar beet worker. The son of immigrants from Jalisco in Mexico, he came with his parents to Colorado in 1918. He eventually settled in Longmont with his wife and raised a family. His parents lived in Longmont also. Here is how he described his early life in Colorado to an interviewer in 1987:

“We came here in 1918 . . . to work in the fields picking [sugar] beets. We worked on various farms. In 1924 I got married. A year later I started to work in the [coal] mines [of Boulder County]. In 1929 I quit working in the mines for a while and went to work for the sugar company [in Longmont], but in the summers I worked in the fields still. . . . Back then you might have worked a day a week or so and earned three or four dollars, but that was enough to support yourself for a whole week. Nowadays you need a lot of money for everything. If you go grocery shopping today a bag of food will cost you $100, so nobody can live with one day’s work a week anymore.”

[Source: Boulder County Latino History Project, Alex Gonzales Oral history interview; Oli Duncan, interviewer, c. 1987. In Duncan, ed., We, Too, Came to Stay, pp. 31–34. Available online at: http://bocolatinohistory.colorado.edu/document/oral-history-alex-gonzales-pt-1]

Questions:

- When did Alex Gonzales come to Colorado?

- What kinds of jobs did he do? Why do you think he changed jobs like that?

- How much did Alex Gonzales earn in comparison to Emilio Ferraro in document 2?

- What did he think about the cost of living (buying groceries, for example), in 1987 compared with earlier in his life?

- Alex Gonzales told this story in 1987. How many years later was that from his arrival in Colorado? Could this time lag affect his memory of the early years?

***

Document 6: Story about Marciano Aguayo, sugar beet worker (betabelero) from Mexico, 1998

Marciano Aguayo left a poor farming community in Aguascalientes, Mexico and migrated to the sugar beet fields along the South Platte River in Merino, Colorado in 1921. Relatives described Aguayo as “muy trabajador”—a very hard worker. After a year’s work in 1929, he had earned $482. Marciano’s son, José, reported in 1998 that he heard his father tell this story about his earlier life:

|

WORD BANK: Accustomed: used to Furrows: small ditches between rows of a plant on a farm Carbide lamp: A light powered by a chemical compound Mounted: placed on Cap: a soft hat |

I was accustomed to waking up at 3 am every morning. I walked to the fields, arriving by first light when one was just able to see the individual beet plants. I would walk in the furrows between the rows, thinning and hoeing two at a time. I continued this pace until well past dark, lighting my way with a carbide lamp mounted on a miner’s cap. I was home by 10 pm every night to catch a few short hours of sleep before repeating the routine all over again.

[Source: Quoted in José Aguyo, “Los Betabeleros (The Beetworkers),” in Vince C. de Baca, La Gente: Hispano History and Life in Colorado (Denver: Colorado Historical Society, 1998), 113]

Questions:

- How many hours a day did Aguayo work in the fields?

- What kind of work did he do?

- Does this work sound difficult?

- He could have chosen to return to his native Mexico. What did you think he stayed and raised a family in Colorado instead?

- Aguayo’s son reported that his father received certificates from his employers praising his hard work. How might that affect his decision to stay?

- What do you think was needed to own your own farm in Colorado in the 1920s? Why do you think Aguayo didn’t become the boss on his own farm?

***

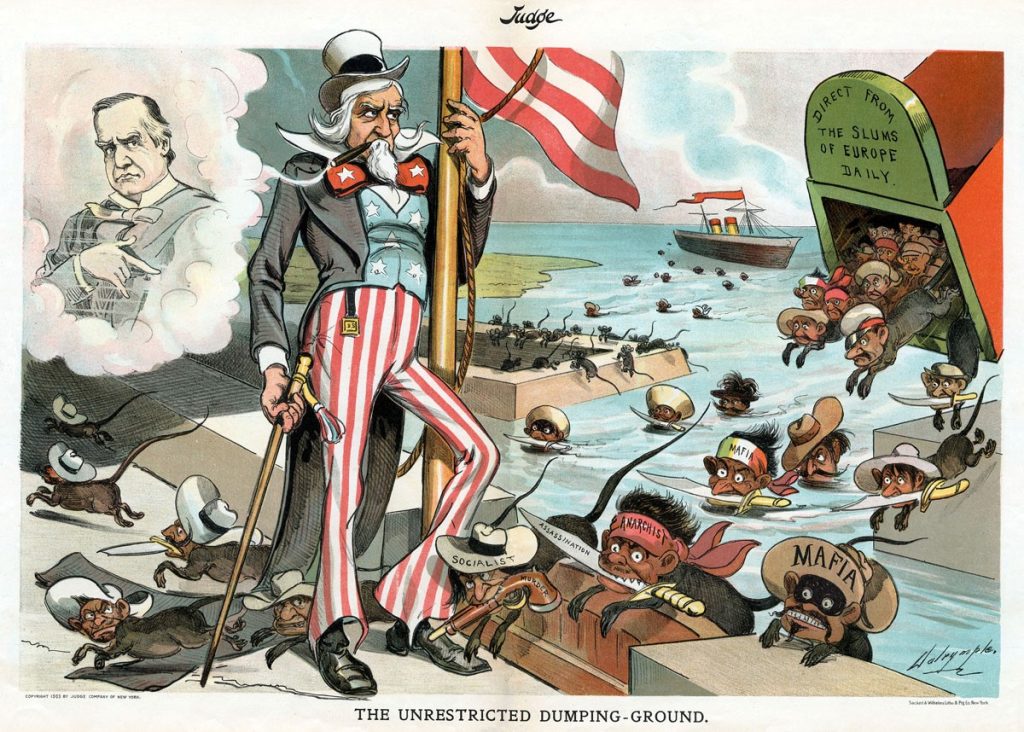

Document 7: Judge Magazine Cartoon, 1903

Artist Louis Dalrymple drew this cartoon about Italian immigrants coming to America in 1903 for Judge Magazine. At this time, the magazine published about 100,000 copies of each issue.

[Source: Louis Dalrymple, “Unrestricted Dumping Ground,” Judge, vol. 4-45, 1903; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Unrestricted_Dumping-Ground._Louis_Dalrymple.jpg]

Questions:

- The tall man next to flag pole was called “Uncle Sam.” How was he dressed? Who might he represent?

- Next to the boat in the harbor is a box that looks like an old-fashioned rat trap. What is written on the box? What caption is written at the bottom of the cartoon?

- How did the artist Dalrymple draw Italian immigrants? Why did he draw them that way, do you think?

- What worries did Dalrymple have about these Italian immigrants? Use a dictionary to look up words, if you need to.

- If this cartoon represents the attitude of some Americans toward Italian immigrants at this time, what challenges did those immigrants face?

- Extra Credit: the figure to the left of Uncle Sam was probably President William McKinley. Check out how he died online. Why might the artist draw him in that puff of smoke from Uncle Sam’s cigar?

***

Document 8: Letter to Colorado Governor about anti-German threats, 1918

Some immigrants faced discrimination when they came to the United States. During World War I, many Coloradans worried about the German-speaking immigrants who worked in the sugar beet fields along the eastern Plains. Germany was the enemy of the United States during that war. Below is a letter from a pastor of a German Lutheran church (St. Paul’s) in Sugar City, Colorado to the Governor. Sugar City is east of Pueblo and near Rocky Ford and La Junta. This pastor typically conducted Sunday school and church services in German, since church members spoke German as their first language.

|

WORD BANK: Demand: forceful request Discontinue: stop Complying: agreeing Engaged in: busy working at Sentiment: feeling Free exercise of: freedom to practice |

[On August 25, 1918] a demand was made upon us by a number of citizens of [Sugar City] to discontinue all use of the German language . . . . [And]giving us the alternative of complying with the demand or having our church property burned down. . . . Nearly all members of our church are German Russians mostly engaged in [sugar] beet raising. They have bought bonds, war savings stamps, given toward the Red Cross, YMCA, Soldiers and Sailors Aid, etc . . . .We are aware of the sentiment against the use of the German language, however, we are also aware that under the constitution of our country we have the right of free exercise of our religion.

[Source: K.F. Weltner letter to Gov. Julius Gunther, August 27, 1918, Colorado State Archives; reprinted in William Virden and Mary Borg, Go to the Source: Discovering 20th Century US History Through Colorado Documents (Fort Collins, Colorado: Cottonwood Press, 2000), 36].

Questions:

- Why did some people in Sugar City threaten to burn down this immigrant church?

- According to the pastor, how did the church members show their patriotism during a time of war with Germany?

- Why did some residents of Sugar City feel the German-speaking workers didn’t belong?

- What might the governor of Colorado have done to deal with this problem? What would be fair, given this was wartime and Germany was an enemy?

- How can the president or governor best promote patriotism among immigrants where there is war happening?

***

Document 9: Japanese American Student Letter from Amache, 1944

During World War II, the United States fought against Germany and Japan. The US Government ordered that people of Japanese heritage living in California, Oregon, and Washington move to prison camps in other states during the war. One of these camps was located in Colorado. About 7,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans lived in this camp, called Amache. While in this prison, young Japanese Americans were allowed to go to school and sometimes compete in sports against other local schools. In November 1944, however, white parents at nearby Wiley High School refused to let their boys play football against the Japanese American team from Amache. One Amache student wrote a letter to complain:

|

WORD BANK: Permit: allow Engaging in: taking part in, playing |

Rather than feeling disappointed over the waste of our many practices, I am rather more disappointed in the 5 boys’ parents who would not permit their sons to play against us because we are Japanese Americans. . . . I hope that in the near future we can get to a better understanding with them and be able to go about engaging in athletic activities without having anyone opposing because of race or color.

[Source: Ken Nakatagama letter, 1944, History Colorado collection. Quoted in Christian Heimburger, “Japanese Imprisonment at Amache,” Primary Resource Set available at History Colorado: https://www.historycolorado.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/2017/amache_primary_resource_set.pdf]

Questions:

- Find Granada on a map of Colorado. Why do you think the US Government would choose to locate a prison camp for Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans there?

- Why do you think that some white parents at nearby Wiley High School did not allow their sons to play football against the team from Amache? Was there a good reason?

- The author of this letter, Ken Nakatagama, was disappointed about the cancelled football game. Why?

- What did Nakatagama hope would happen?

- How can a football or baseball or basketball game between different kinds of people help ease suspicions or build friendships?

***

Document 10: Hart-Celler Act, 1965

In 1965 the U.S. Congress and President Lyndon Johnson changed the rules for immigration into the United States. This new law, the Hart-Celler Act, affected the kinds of immigrants who could move to Colorado. The section of the 1965 immigration law below described a special situation for refugees from other countries. These are generally people fleeing their home countries because of violence or serious dangers. Some refugees to the United States wanted to escape from communism in their home countries. Communist countries drastically limited freedom and often imprisoned people who disagreed openly with the government.

|

WORD BANK: Persecution: abuse on account of: because of Uprooted: displaced or forced to move Calamity: disaster |

[Immigration officials can allow special entry to the United States to immigrants who] because of persecution or fear of persecution on account of race, religion, or political opinion . . . have fled from any Communist or Communist-dominated country or from any country within the general area of the Middle East and are unable or unwilling to return to [that] country . . . on account of race, religion, or political opinion.

[Immigration officials can also allow into the United States those immigrants who] are uprooted by catastrophic natural calamity.

[Source: Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1965, Public Law 89-236, U.S. Statutes at Large, 79 (1965): 913. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-79/pdf/STATUTE-79-Pg911.pdf]

Questions:

- This new immigration law seems to give a special opportunity to those who are persecuted or fear persecution. What are some reasons in the document that people fear persecution?

- What might have motivated Congress and President Johnson to create this new immigration law?

- What parts of the world were people coming from?

- Why might these immigrant refugees want to come to Colorado?

- Do you have any guesses about where refugees to Colorado come from today?

***

Document 11: Table Listing Refugees in Colorado, 1980 – 2017

Since 1980, Colorado has welcomed a wide range of refugees from other countries. These are generally people fleeing their home countries because of violence or serious dangers. Once the American government grants these refugees permission to enter the United States legally, they get help from specific states like Colorado to resettle. The Colorado state government, in fact, has created a program to help refugees adjust. This refugee assistance program counted the following numbers of refugees from different parts of the world:

East Asian Countries

| Original Country of Refugees | How many Came to Colorado between 1980 and 2017? |

| Vietnam | 10,788 |

| Burma | 5,314 |

| Laos and Hmong | 4,774 |

| Bhutan | 3,684 |

| Cambodia | 2,269 |

| Other East Asian countries | 559 |

| Total Refugees from East Asia | 27,388 |

African Countries

| Original Country of Refugees | How many Came to Colorado between 1980 and 2017? |

| Somalia | 4,646 |

| Ethiopia | 2,596 |

| Congo | 1,656 |

| Sudan | 1,204 |

| Other African Counties | 2,962 |

| Total Refugees from Africa | 13,064 |

European and Central Asian Countries

| Original Country of Refugees | How many Came to Colorado between 1980 and 2017? |

| Soviet Union or Russia | 6,083 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2,131 |

| Other European Counties | 2,832 |

| Total Refugees from Europe and Central Asia | 11,046 |

Middle East and South Asia

| Original Country of Refugees | How many Came to Colorado between 1980 and 2017? |

| Iraq | 3,765 |

| Afghanistan | 1,853 |

| Iran | 762 |

| Syria | 270 |

| Other Middle East and South Asian countries | 146 |

| Total Refugees from the Middle East and South Asia | 6,796 |

Latin America

| Original Country of Refugees | How many Came to Colorado between 1980 and 2017? |

| Cuba | 1165 |

| Columbia | 125 |

| Mexico | 31 |

| Other Latin American Counties | 211 |

| Total Refugees from Latin America | 1,532 |

| Total Refugees to Colorado, 1980 – 2017 | 59,910 |

[Source: Colorado Refugee Services Program Online Data, 2017: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_jdz6ky4pADOBzRxF_HjslaiAF0RBkDJ/view]

Questions:

- What five countries of the world have sent the most refugees to Colorado?

- Which of the regions listed above (East Asia, Africa, Europe, etc) sent the fewest refugees?

- What kinds of events might push refugees from their home countries?

- Why might refugees want to come to Colorado today? What does the state offer them?

- What challenges will refugees in Colorado face today?

- Compared to earlier sources, does this source show a more inclusive or exclusive side to Colorado? How?

***

How to Use These Sources:

These sources allow students to explore some important aspects of immigration to Colorado in the twentieth century. There are opportunities to consider push and pull factors that motivated immigrants as well as reception by native-born Coloradans. Students can begin to consider anti-immigrant prejudice at key moments in Colorado history and how that has changed over time. Students might create a T-chart to list “Push” and “Pull” factors as they read the different documents. Ultimately, they might organize short quotes or phrases from these sources into a Found Poem on immigration to Colorado. To make a Found Poem, students can pull words or phrases from different documents and group them in a new poem. For more ideas about Found Poems, please see this Library of Congress guide: http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/poetry/pdf/teacher_guide.pdf

Option 1: The first four documents offer both visual and written sources on Italian immigration and the promise of mining work. Document 1, the photograph by Lewis Hine, pictures Italian immigrants at Ellis Island. It suggests some typical challenges for historians: we don’t know the names or stories of the men pictures, only that they are immigrants, starting a new life phase in America. Document 2 gives us an oral history of one Italian immigrant who came through Ellis Island and ended up working coke ovens near Trinidad. Could the immigrant in that oral history be pictured in the photograph? How might we decide? Even if the dates of the photo and Ferraro’s arrival in New York don’t match up exactly, could we use that photo to help us picture what Ferraro might have looked like? When reconstructing the lives of ordinary people, and not just presidents, we often rely on incomplete evidence and have to fill in some gaps with some evidence-based imagination.

Students could consider all four of these first four documents to consider push and pull factors for Italian immigrants. They could also begin to make a list of the kinds of work these new immigrants were doing.

Option 2: Adding documents 5 and 6 to student projects will introduce another immigrant group—Mexicans. These two oral histories can help students explore the experience of sugar beet workers. These immigrants contributed to the agricultural development in the state. How were their experiences similar? How might the work of Mexican sugar-beet workers differ from an Italian mine worker near Trinidad? What would it be like to engage in both occupations each year?

Option 3: Documents 7, 8, and 9 address discrimination and challenges. There is a visual source (cartoon) and two stories from immigrants who resisted prejudice. Students could study the cartoon (Doc 7) before comparing that message with the picture of Italian immigrants they have from the first few sources. The Lewis Hine photograph is more sympathetic while the Dalrymple political cartoon is obviously hostile toward immigrants. Why were they so different in their view of immigrants?

Wartime contexts seem to create new challenges for immigrants. Document 8 on German-speaking sugar-beet workers and Doc. 9 on Japanese and Japanese American internment both show this in different ways. What challenges did each immigrant group face during wartime? Both were considered potential enemies. How did each respond? Students could consider the question: what could Coloradans have done differently about these immigrants during wartime?

The last sources address the changes in immigration policy in the United States since the 1960s. The Hart-Celler Act in Document 10 helps create the opportunity for refugee migration into Colorado that is the topic of Document 11. Students can get a sense of the range of countries of origin for recent immigrants and refugees in that latter source. The table in Document 11 will require some math skills to interpret. After considering the cause and effect link between these documents, students might speculate about the change in reception. Why have Coloradans been more welcoming of refugees in the last thirty-five years? How about today?